Something miraculous happened earlier this month when culture writer and Harvard professor Namwali Serpell published her piece “The New Literalism Plaguing Today’s Biggest Movies” in The New Yorker….people actually read it! And engaged with it! Even two weeks later, my Twitter feed is filled with healthy cultural discourse around Serpell’s observations. This edition of Cory’s Reads marks my own contribution to that discourse, which has been unfortunately muddied by the incoherence of Serpell’s own argumentation.

Indeed, the headline of the piece posits an idea with which many of us have likely wrestled in recent years. Movies (and TV shows) have grown increasingly obvious and overwritten in recent years. Art does seem to be insulting our intelligence, and a pervasive sense of literalism does seem to be undermining our favorite works. But Serpell bizarrely dwells not on the Netflix programs in which characters explicitly state their actions, as mandated by the powers-that-be, nor on the Marvel Cinematic Universe, whose juvenile writing has been dumbing down its adult audience for over a decade. She instead takes aim at 2024’s lineup of Oscar nominees, including Best Picture winner Anora and cinephilic darlings The Brutalist and Nickel Boys. Serpell almost willfully misinterprets such projects, accusing the former of heavy-handedly announcing its Cinderella parallels, and the latter of incorporating overly explanatory archival footage. Readers of Cory’s Reads #42 already know how much I vehemently disagree with the Nickel Boys slander, but even the Anora accusation is a hilarious failure of cultural criticism. That film’s relationship with the classic princess tale is far from a literal one, and its acknowledgment of the parallels only serves to complicate the plight of its title character. If even that explanation seems unnecessary and self-evident, I struggle to see the issue with a film making itself lucid and available to its viewership.

Legibility is not to be confused with literalism, and to disregard entire films solely because you are capable of interpreting them strikes me as anti-art and anti-intellectualism. Serpell writes off such a defense: “artists and audiences sometimes defend this legibility as democratic, a way to reach everyone. It is, in fact, condescending.”

My own personal allergy to condescension in media compels me to agree with Serpell on the surface, if only she had not collected all the wrong evidence to support her claim. In fact, a project like Nickel Boys that can balance both legibility and complexity deserves our praise, not our derision. By the time Serpell uplifts Conclave as a beacon of subtle and unpredictable storytelling, it becomes clear that the author’s promising premise has been sacrificed in favor of her own personal taste. I am wary of my own tendency to contort arguments here at Cory’s Reads in order to accommodate my favorite films, but at least I have the excuse of independently publishing my long and winding diatribes! I am quite frankly surprised that The New Yorker would publish something so illogical and incomplete — an earlier version of the piece even claimed that A Complete Unknown ends with real-life footage of Bob Dylan.

Spoiler: it does not!

Even as someone who identifies as quite media literate, I remain concerned with the analytical skills not of Harvard professors, but of the wider viewing public. Potential insults to our intelligence notwithstanding, perhaps the democratization of the meaning-making process is not such a bad thing.

Alas, I have dedicated enough space to criticizing the work of a writer whose heart is seemingly in the right place. Serpell may have wasted her opportunity to highlight the degradation of our cultural complexity, but her initial identification of the development has facilitated several great online discussions (as well as a fun stretch of my latest podcast episode!) and merits thoughtful consideration nevertheless.

While some elements of the New Literalism — was there ever an Old Literalism, by the way? — certainly stem from societal malaise and corporate greed, I wonder if a literal approach to storytelling has earned its place in the zeitgeist after all.

If you were brave enough to click that link to my podcast It’s All Film and Games (there it is again for good measure), you know that I am a fan of Bong Joon-Ho’s latest film Mickey17. The Korean auteur’s sprawling and occasionally sloppy sci-fi epic is anything but subtle, loudly reiterating several of the director’s favorite topics: class inequality, corporate malfeasance, and capitalism as a dehumanizing meat grinder. Its blunt voice and slapstick sensibilities have rendered Mickey17 divisive amongst even the most loyal Bong acolytes, but I found the film’s forthrightness refreshing. When Nasha Barridge (Naomi Ackie, in her best performance yet) delivers the film’s most powerful monologue with a record amount of fucks-per-second — I believe the phrase “fuck you, you fucking fuck” is uttered at one point — it becomes clear that Bong and his collaborators have embraced the explicit in more ways than one. Nasha’s angry rant taps into a broader frustration so many of us are feeling today, particularly as it is directed towards Mark Ruffalo’s Trump-coded Kenneth Marshall.

Mickey17 is laughably legible, to the extent that it may not build upon the anti-capitalist messaging that Bong introduced onto the mainstream with 2019’s Parasite and which has been repeated ad nauseum by far inferior films in the six years since. Serpell would likely lump that legibility in with the New Literalism, but is that such a bad thing? Perhaps our moment calls for such a direct approach to thematic storytelling. With a filmmaker at the helm as bold and expressive as Bong — or RaMell Ross or Sean Baker or Brady Corbet, for that matter — literalism does not preclude active viewing. Whereas projects from the likes of Netflix and Disney may encourage a kind of passivity in their audiences, Mickey17 and Serpell’s suite of other New Literalism artifacts still leave room for an interpretive process for which the vast majority of viewers still clamor.

Indeed, the meaning-making process should be participatory, but there is value in carrying out that process under the auspice of a trusted artist. I suspect Serpell is drawn to Conclave because the film is nonjudgmental in its thematic tour through the gossipy halls of the Vatican. While I found the film to be lacking in perspective — largely because director Edward Berger is decidedly not on my own personal list of trusted artists — I do see the appeal of the artist as sherpa, gently leading us on a personal journey rather than explicitly instructing us on right and wrong.

We get enough demagoguery in our daily lives, after all.

But arguably the biggest cultural phenomenon of 2025 has been season 2 of Dan Erickson and Ben Stiller’s Severance, a show whose intrigue flows from the increasingly cryptic conspiracy at its core. While the second season certainly expanded the show’s much-deserved cultural footprint, it also grafted several other mysteries onto its emotional center. There are diminishing returns to watching this puzzle box unfold, as the only true reward for watching Severance is that you get to watch more Severance. Mysteries evolve but are never quite solved, and yet audiences are entranced by a show that has welcomed fan participation like never before. Scouring Reddit or TikTok like a crazed Macrodata Refiner is nearly a prerequisite to enjoying the Apple TV+ series, and the goodwill that Erickson and Stiller (but mostly Stiller) have generated with viewers has afforded them an embarrassing degree of leeway in unfurling the show’s labyrinthian plot. Storytelling missteps are rarely flagged or criticized, only incorporated into fan theories and predictions. This aspect of Severance makes the show feel almost revolutionary, a show uniquely fit for our times. Transmedia has lingered for decades now, second screens and comic book spin-offs splintering storytelling from major studios and networks. But Severance is less interested in spreading its story across multiple mediums, but rather in employing audiences in its laborious interpretive process. At times, it feels as if we are doing the dirty work for a show that may not have it all figured out. After all, what the hell even is reintegration anyway?

Like Mickey17, Severance does offer a visionary metaphor for modern life. Both properties explore the dissolution of self beneath the drudgery of capitalism, the absurd pressure to create a new version of yourself, freed from your ego, optimized for the market. We saw it with The Substance and A Different Man in 2024 as well — the doppelganger deployed as the most desirable iteration of the self.

That’s good shit! But are we properly plugged into the profound implications of a show like Severance? Have our inquiries drifted too far from what the show actually wants to say? We are trying to untangle its narrative knots, but to what end?

Innies and outies alike are united in unpacking our latest TV obsession, suggesting there is still an appetite amongst consumers for complex, perhaps even indecipherable, messaging.

But can there exist a middle ground between our thankless investigations and our passive acceptance of spoon-fed slop?

The best television show of 2025 is Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham’s Adolescence (Netflix), impossibly patient and compassionate in its balanced dissection of an unspeakable tragedy. Each of the series’ four episodes is shot in a single continuous take. Director Philip Barantini explained that creative decision to Hugh Hart of The Credits:

“I didn’t ever want the one-shot to be at the forefront of the show as a spectacle, like, ‘Look how clever we are,’ but there are just many distractions nowadays and we’re all so used to watching TV or film even at home with one eye on the screen, and one eye on the phone. With Adolescence, I wanted the audience to go on an immersive journey that unfolds in real time just as it’s unfolding for the actors in real time. [The single-take] creates a tension and forces a perspective on the audience to where they can’t look away, even if they feel anxious or awkward.”

Adolescence is respectful of our intelligence. Barantini understands that viewers have the means to reflect upon the moving image just as we have since film’s inception in the late 1800s, if only those images actually welcomed it. That Adolescence is a Netflix Original is all the more surprising, surrounded by shows for whom the audience’s attention is an afterthought. With such a thematically dense and unflinching script, one could accuse the miniseries of adopting the traits of New Literalism. However, the show rather benefits from a vital sense of immediacy, stemming from its open embrace of zeitgeisty terms like “incel” and “Andrew Tate.”

As teens translate complex emoji-based codes into haunting mandates from the manosphere, the bizarre intricacy of those text messages and Instagram comments renders them incomprehensible for those of us over the age of sixteen. In the hands of lesser writers, these explanations might have come across as cringey or far-fetched, but there is an attention to detail in Adolescence that helps reframe Serpell’s New Literalism as unsettlingly urgent, as opposed to condescendingly didactic. The show stands out as a blueprint for the kind of social-issue-driven storytelling that our moment calls for. While the New Yorker piece suggests there will always be audience members who recoil at creative attempts to resonate with the crises of our time, our collective willingness to sift through the sophisticated mysteries of a show like Severance also suggests a societal hankering for media analysis that may be best applied in the more coherent contexts of Mickey17 and Adolescence, where the legibility of those worlds can be loudly cemented as relevant and real.

At its core, Severance is similarly significant in its echoes with the zeitgeist. Its greatest strength is also its greatest weakness, adorning its anxieties around corporate culture with elaborate sci-fi window dressing. I sometimes worry its Reddit-brained audience has lost sight of the show’s urgent underpinnings, and so long as we are doing the dirty work for a show that is, somewhat ironically, interested in liberating us from the tedium of our labor, I wonder if there is an honesty to products of the so-called New Literalism which transcends any preoccupation we may have with their salience or simplicity.

As much of our media is dumbed down and diluted by studios whose Hollywood roots have given way to Silicon Valley stakeholders, this discussion remains ongoing. I reserve the right to sound the alarms if our endless onslaught of content grows exceedingly shallow, a legitimate possibility in an era defined by its powerlessness. For now, I believe there is utility for the kind of storytelling that grabs us by the shoulders and shouts in our face.

As Nasha Barridge might say to no one in particular…

“fuck you, you fucking fuck!”

Letterboxd Review of the Month

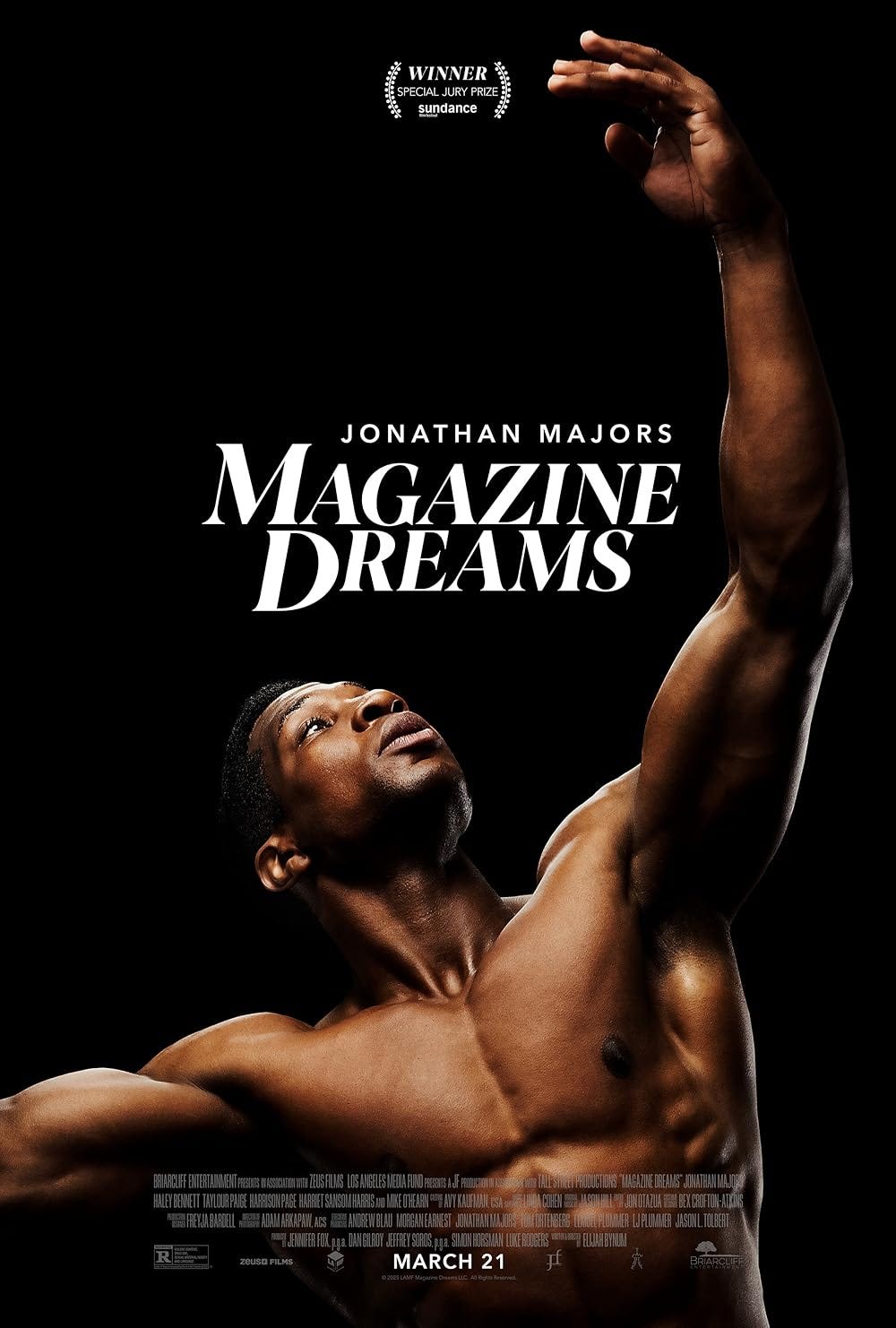

I met the composer for this film at a work event recently (Jason Hill, who just so happened to be the lead singer of Louis XIV!) and the conversation compelled me enough to check it out despite the controversy surrounding Jonathan Majors. Hill's score is genuinely epic and haunting, even taking on more and more of the heavy lifting as the film begins to overstay its welcome. A good deal of bloat aside, Magazine Dreams is wildly gripping, treading familiar territory beat to beat (Whiplash, Nitram, and Joker are the most obvious comparisons, but just about any Paul Schrader film would do), yet emerging as a uniquely modern take on masculinity and self-determination. But whereas other films may have offered us an emotional lifeline in the form of upbeat jazz, national identity, or comic book connectivity, this one is strictly suffocating. That growing pit in your stomach throughout the entirety of this film is simultaneously unsettling and addictive, a product of not just the sheer involvement of its troubled star, but also his uncomfortably magnificent performance.

It truly is a shame that Majors has proven to be a piece of shit, as I cannot recall the arrival of an actor with such intense screen presence in quite some time. His rapid rise through Hollywood's ranks felt exciting and fresh, and the continued evidence of his talent here in Magazine Dreams only further underscores the tragedy of his consequential fall. He equips himself unsurprisingly well as a violent and unstable bodybuilder, unafraid to contort both his body and face in service of our own fear and disgust. Majors' intensity does not always feel congruous with director Elijah Bynum's oddly muted handling of such dark material, but it lends the film a sense of both tenderness and misery that would likely have been missing otherwise. There is an unpredictability to Majors' Killian Maddox that makes him one of the more terrifying yet tragic characters in recent memory. Watching Magazine Dreams in a mostly empty theater save for me and a few other dudes felt legitimately vile and unsafe, an unfortunate yet undeniable testament to the sacrificial willingness of its lead performer, who, perhaps fittingly, may never act in a mainstream project again.

Follow me on Letterboxd at @creid61, and keep up with the rest of my work on Instagram at @coryreid6125.

I am on BlueSky now as well! Follow me at @coryreid.bsky.social.

You can also support my work over at Buy Me a Coffee.

![Robert Pattinson's Romance Storyline In Mickey 17 Explained By Love Interest Naomi Ackie: "[It's] About Defending The Underdog" Robert Pattinson's Romance Storyline In Mickey 17 Explained By Love Interest Naomi Ackie: "[It's] About Defending The Underdog"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!YD5_!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1454bdcb-2670-4e17-a31a-3f3bdd17e050_3764x1882.jpeg)