Cory's Reads #42: Telling True Stories

Iranian director Mohammed Rasoulof has made a movie that matters, and he risked imprisonment to do so.

It could be said that the overall project of this newsletter is a kind of reckoning — an endless inquiry into the significance, or lack thereof, of contemporary cinema. Anyone following my work over the last several months is surely familiar with that all-too existential sense of doubt seeping into my cultural worldview. Does film still matter? Does writing still matter? Are these the appropriate tools of our time in tackling our societal ills?

I reserve the right to continue waffling on these questions every month for as long as I write. And yet, every once in a while, such uncertainty mercifully yields to far greater and more pressing questions. When the right film comes along and asks them, my own philosophical concern over the medium’s vitality can seem trivial, like a pet project irresponsibly abstracting the ideas and implications of a genuine cinematic achievement. It is easy to pontificate about our cultural powerlessness when discussing films like The Fall Guy and Deadpool and Wolverine, but the best film of 2024 is a marvel not only because it is gorgeous and gripping, but because it establishes director Mohammad Rasoulof and his entire cast and crew as a legitimate team of real-life heroes. The Seed of the Sacred Fig is filmmaking as an act of bravery and rebellion. It is art as a form of protest, storytelling as a form of revolution. Even as my pessimism persists to varying degrees, it is hard not to be romantic about a film as bold and urgent as this one.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig follows the growing tensions within a single family in contemporary Iran. When father Iman — a newly appointed investigating judge on the country’s Islamic Revolutionary Court — loses his government-issued handgun, he suspects his wife, Najmeh, or his daughters, Sana and Rezvan, have stolen it. As the real-life Mahsa Amini protests unfurl on the streets below, the family finds their relationships and their worldviews tested like never before. The film was shot in complete secrecy over about 70 days. Towards the end of production, Rasoulof was forced to flee the country on foot after being charged with an eight-year prison sentence. He completed post-production on the project in Germany, who helped secure the film an Oscar nomination for Best International Film.

Because Rasoulof and his team could not shoot in public, he and editor Andrew Bird incorporate actual footage of the violence during the 2022 protests. Even stripped of its unbelievable behind-the-scenes story and its urgent political context, The Seed of the Sacred Fig is a taut and twisty thriller, but its ingenious interweaving of real-life footage is what makes it an indispensable artifact of Iranian and global history. Rasoulof may be the one facing imprisonment for his work, but his clever integration of this footage is also a testament to the work of the amateur filmmakers who have earned that designation simply by opening their phone cameras and recording history.

Indeed, filmmaking is writing a scene and composing a shot and stitching a story together. But it is also being in the right place at the wrong time and being brave enough to capture the truth.

In his role as investigating judge, Iman must record confessions from tortured civilians. Eventually, he turns the camera towards his own daughters in his hapless attempts to verify his own paranoia. In a film preoccupied with these testimonials of truth, the presence of the same violence one might encounter simply scrolling through Instagram — the clips are sometimes presented in this way, as Sana and Rezvan covertly DM such horrific posts to one another — is a chilling reminder of how (and where) facts are established in the first place. Iman and Najmeh cannot believe their daughters’ distrust of what they see and hear on TV, but they have not borne witness to the violence like the young girls have. When Najmeh finally does see the damage caused by the Iranian government and her husband’s line of work, she begins to understand Sana and Rezvan’s more modern perspective.

And now we get to bear witness all the same. For an international audience, it is the least we can do. Sacred Fig does a real service to the courageous men and women documenting their harsh reality for all to see. To relive these memories cannot be easy for an Iranian audience, but there is power in Rasoulof’s visual affirmation of his nation’s trauma.

No, you are not crazy, Rasoulof’s film tells his people. You are being lied to. We do deserve a better and safer world.

The message is delivered with uncanny urgency — it is rare that we get a fictional film so immediately connected to our political present. Instead, documentary is more often tasked with covering current events.

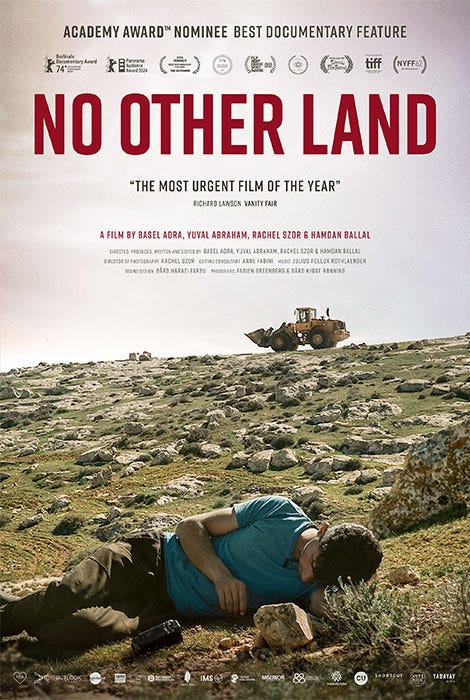

The last two Best Documentary winners at the Oscars are 20 Days in Mariupol in 2024 and Navalny in 2023. Mariupol is a horrifying work of reportage, bringing viewers to the frontlines of the war in Ukraine. Navalny is a real-life political thriller, tracing the poisoning of the titular Russian opposition leader. This year we are likely to see No Other Land recognized in the category, a brave account of Israel’s gradual destruction of occupied territory in Masafer Yatta, a small collection of villages in the West Bank. The film has yet to secure US distribution, and it is sadly easy to see why. Like Sacred Fig, the film’s footage is undeniable evidence of one government’s evil and corruption. America’s embarrassing support and preservation of the Israeli brand would appear exceedingly misguided if mass audiences had access to the film. Fortunately, it is playing in a select few theaters across the country. Also like Sacred Fig, the film has a chance to become one of the defining political documents of our time.

Written and directed by an Israeli-Palestinian collective, No Other Land focuses on the friendship between two of them: Palestinian activist Basel Adra and Israeli journalist Yuval Abraham. Their relationship is unsurprisingly complex, rife with both admiration and tension. Basel has a firm belief that a high-profile piece of news — an acclaimed documentary, perhaps? — could be enough to draw global attention and convince the United States to pressure Israel to end the occupation. Yuval may have a similar conviction, but he more often laments the limited reach of his own articles. He insists that all he wants to do is help Basel and the Palestinians, but Basel can’t help but resent Yuval’s freedom to come and go between Masafer Yatta and his home in Be'er-Sheva. No matter how noble his cause may be, Yuval cannot escape his own privilege and naïveté.

Basel likely has more in common with fictional sisters Sana and Rezvan than he does Yuval. Like those teenage girls, Basel is glued to his phone, intaking footage of all the tragedy in his community and beyond. Even as an activist who continues to bear witness to these atrocities firsthand, Basel concludes that there is nothing for him to do besides be on his phone. Yuval cannot understand it — the action seems passive and masochistic. He may be right, but Basel’s addiction to his phone also suggests a strange comfort in staying up-to-date with your own reality, in allowing the captured image to authenticate that which your eyes can barely believe.

For Yuval, it is not enough to bear witness to suffering. He must make others a witness as well. As distant audiences who may be content to bypass both responsibilities altogether, we are fortunate to have filmmakers like Rasoulof and the foursome behind No Other Land, who leave us no choice but to comprehend the suffering of others. We rely on documentary footage as a necessary means of verifying our present reality, to the extent that we are comfortable perceiving our reality whatsoever.

On the surface, Rasoulof’s incorporation of actual footage is necessitated by the censorship that he and his collaborators had to circumvent in riskily crafting Sacred Fig, filling in narrative gaps where the filming of large-scale set pieces was not possible. But it also allows the film to uniquely straddle the line between documentary and fiction. This gripping story may be scripted, but as the unscripted sequences continue, a realization settles in for the audience: oh shit, this is real. Plenty of films tell true stories, but very few of them manage to so directly confront audiences with the weight of those true stories.

I am reminded of Spike Lee’s ending to his 2017 film BlacKKKlansman, in which a historical drama is brought into dramatic collision with the present day. As real footage of white nationalists in Charlottesville flashes before our eyes, we are left feeling vulnerable to the horrific events that preceded it, no longer safe in the assumption that what’s past is past.

Lee has always had a knack for forcefully — but not unnecessarily — extending his film’s themes into our current moment. He employed a similar trick with 1989’s Do the Right Thing, displaying two competing quotes from MLK and Malcolm X once the film’s tragic finale has unraveled. The other great film of 2024 is Nickel Boys, and its director RaMell Ross seems to have a bit of Spike Lee inside him, with a dash of Terrence Malick and Khalik Allah for good measure. Nickel Boys utilizes archival footage in a completely different way from The Seed of the Sacred Fig, contextualizing its fiction within the true stories that inspired it. Real-life news reels recall the actual Dozier School for Boys upon which Nickel Academy is based. Footage of the moon landing draws a parallel between the hopes and dreams of young Black boys in 1960s America, and the relative pessimism of those entrapped in the Nickel Academy’s harsh surroundings. Cutaways to old-timey advertisements remind us that young Black children were once not-so-jokingly referred to as alligator bait in the 19th and 20th centuries. Like Rasoulof and Lee, Ross ensures that his film is in constant collision with our world.

The same could be said for The Brutalist director Brady Corbet, who interjects into his three-and-a-half hour epic a few archival sequences from a 1950s Pennsylvania tourism film called Land of Decision.

“Perhaps no state or nation in the entire history of man has been the deciding ground of so many human issues as the state of Pennsylvania,” exclaims the film’s booming narrator over visuals of steel mills and smokestacks. But as László Tóth (Adrien Brody) settles in Doylestown, PA (!!!) to build a community center under the patronage of wealthy industrialist Harrison Van Buren, his circumstances quickly come into conflict with the optimism of these archival excerpts. The effect is therefore an ironic one. Whereas the footage in Sacred Fig works to verify the horrors of the present, Nickel Boys and The Brutalist dig into the historical archives in order to interrogate the dominant ideologies of the past.

The hybrid nature of these films secures them a kind of incisiveness that pure fiction cannot always achieve. At the risk of sounding reductive, we live in a time where reality can often seem stranger (and scarier) than fiction — just ask the courageous filmmakers behind No Other Land. Who has time for the imaginary when your own government is gaslighting you into giving up your home?

Our moment is defined not only by its growing instability, but also its outright absurdity. It is therefore unsurprising that this latest wave of filmmakers are sorting fact from fiction, unsatisfied with the ho-hum nature of traditional cinematic storytelling. With our world’s most powerful images gliding through our TikTok and Instagram feeds, it is easier than ever to question the value of pictures projected on the big screen. But when I first watched those vertically formatted clips in No Other Land and The Seed of the Sacred Fig play out in a dark movie theater, I was overwhelmed by their magnitude. They were no longer skippable nor could my attention be divided between them and an episode of The Traitors playing elsewhere. Nearly swallowed by the wasted black space surrounding it, the footage was a welcome disruption of the typical viewing experience. Suddenly, aesthetics felt irrelevant. These images were too urgent and impactful to project neatly onto the screen!

The sheer size of the theatrical screen ensures movies a magnitude that few other mediums can achieve. I am not sure that makes them an effective tool for our times, but they are big. And being big is pretty cool too.

Check out my debut article for IndieWire HERE!

Letterboxd Review of the Month

An overwhelming tribute to the perseverance of oppressed Palestinians in the face of decades-long destruction and displacement. I naively entered the film expecting it to overlap with the post-October 7th escalation of the conflict over the last year-and-a-half, but it crucially takes place almost entirely before the 2023 attack.

This is and always has been ethnic cleansing.

Basel, Yuval, and the rest of their collective have put together a legitimately gripping documentary, with clearly defined characters and several provocative questions around activism, journalism, and suffering.

Having now seen the film, it's unfortunately pretty obvious to me why it never secured US distribution. I'm still not entirely sure how it ended up playing at my local Laemmle here in LA, but if you have the opportunity to see it in a nearby theater, please do so. It's also available to torrent, which I think is justifiable insofar as it is our responsibility to bear witness to atrocities worldwide.

Follow me on Letterboxd at @creid61, and keep up with the rest of my work on Instagram at @coryreid6125.

I am on BlueSky now as well! Follow me at @coryreid.bsky.social.

You can also support my work over at Buy Me a Coffee.